UMD Researchers Are Creating a Bio-Nose That Smells for Real

The toddler game “got your nose!” brings gales of laughter as we pretend to snatch the facial feature. But a real-life ability to transport the sense of smell elsewhere—and even enhance it beyond normal human limits—could help in activities ranging from cooking to sniffing out chemical hazards to tracking the location of a lost person.

Now, a UMD research team’s ambitious “bio-nose” project aims to create a portable, biologically based device capable of identifying odors in the built environment, backed by a four-year, $2 million grant from the National Science Foundation.

“If we had handheld devices that could recognize complex odors, a lot of things would be possible,” says Elisabeth Smela, a professor of mechanical engineering who is leading the project. “There are applications in food, wine, perfumes, medical diagnostics, homeland security, agriculture, mold detection and more.”

The interdisciplinary team also includes Ricardo Araneda, a professor of biology; Pamela Abshire, a professor of electrical and computer engineering; David Tomblin, director of the College Park Scholars Science, Technology and Society program; and Abhinav Shrivastava, an assistant professor of computer science with an appointment in the University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computer Studies.

Shrivastava’s contributions will involve developing the complex computational algorithms needed to analyze the concentration response curves to a panel of odorants, which are then compared to the known responses of the corresponding olfactory sensory neurons.

He will also develop powerful machine learning tools to discover how a collection of cells reacts when exposed to various odors, a process needed to identify the source.

“Modeling complex interactions between odors to understand how those interactions alter response patterns is extremely challenging,” says Shrivastava. “These problems do not manifest themselves in standard computer vision datasets, and we are excited to develop solutions that can have a broad impact.”

Various species—including dogs, humans and insects—have an extraordinary capacity for smell, allowing them to distinguish an extensive array of odors across different environments, the researchers say. To take advantage of nature’s capacity for olfactory reception and scent recognition, the UMD team is developing a sensor based on living cells.

In the past, using cells for this type of application has been challenging. Mammalian cells need to be fed and held at body temperature to be kept alive, necessitating a more practical approach.

“Think about the yeast that you keep dried at home. Wouldn’t it be nice if we had some cells that we could keep dry until we were ready to use them?” Smela asks.

The team’s collaborators at the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) in Japan created an insect-based cell line capable of just that. The cells can be desiccated, or dried, and then re-animated with the addition of fluid at room temperature. Such cells don’t normally express olfactory receptors, so the NARO researchers added the genes into the cell line to allow them to sense odors.

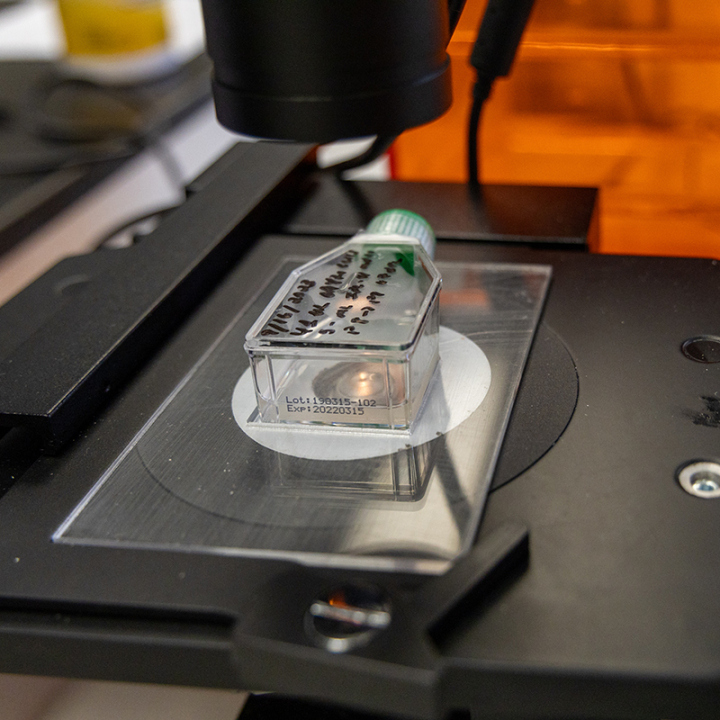

Currently, the team is studying how the cell line responds when it is introduced to different liquids—one step of many on the way to developing a fully usable bio-nose device.

—This news brief is adapted from a story published in Maryland Today.